Erin Becker

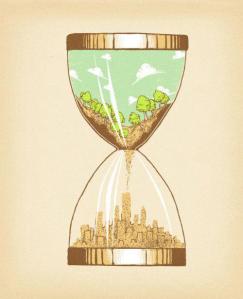

As of recently, dramatic impacts on the earth have been brought to attention regarding issues pertaining to the destructive forces of humans on the environment; the term used to describe this period of time is called the Anthropocene. Though scientists are not exactly sure of the starting point of this “epoch,” some like to say that it may have been a result of the industrial revolution, meaning it began around mid 1700’s. Though humans have impacted the earth since the beginning of time, never have they impacted it more than they have in this present day and age. There are many different aspects that make up the Anthropocene, but I am going to focus on one in particular, that being conservation and why the instrumental value of nature is an essential factor to conservation. Instrumental value pertains to the value one can take from some physical or abstract thing. This value can be received directly from the object or indirectly. Instrumental value can be contrasted with the term “intrinsic value”, where an object holds value in and of itself. In my paper I will be discussing the contents of four different sources that focus on conserving natural resources and the role that instrumental value plays in these conservation methods. I will also discuss the ethical stance each source takes regarding conservation and the instrumental value of nature as well as my own opinion on the matter.

The first article I am going to talk about, “Conservation for the People” by Kareiva and Marvier focuses on the importance of conservation for human well-being. Some of the examples that are used in this article show how humans are directly affected by instrumental value as well as indirectly affected. Though protecting the environment for its instrumental value may sometimes be associated with negative connotations, Marvier does an excellent job explaining the benefits of conserving nature. One example states that “Ecosystems such as wetlands and mangrove stands protect people from lethal storms; forests and coral reefs provide food and income; damage to one ecosystem can harm another half a world away as well as the individuals who rely on it for resources or tourism revenue.” Many of these examples indirectly benefit humans, but they still hold high importance for obvious reasons. Marvier goes on to explain how the economic benefits afforded by ecosystem services are most needed by developing nations. She states that “These countries derive substantial income from timber, fiber and agriculture; forestry and fisheries are typically five to 10 times more important as components of national economies for such nations than for the U.S. and Europe” and that “Maintaining the environment is the key to alleviating poverty for the world’s 750 million rural poor.” Framing the effects of conservation like that makes it seem like conserving the environment for its instrumental value is a no brainer. It also gives this type of conservation strong ethical support. Marvier concludes with saying, “We must be realistic about what we can and cannot accomplish, and we must be sure to first conserve ecosystems in places where biodiversity delivers services to people in need.” It is clear to see where Marvier’s purpose of encouraging conservation comes from, and it is hard to disagree with her stance. All of the examples she provides shed positive light on nature’s instrumental value, and presenting conservation in the way that she did was a smart method in order to connect with people that might have been skeptical about conservation. At the pace that humans are burning through nature’s resources, it is critical that we do our best to conserve what we can and slow down the process of using these resources for our benefit. Doing this seems ethically pleasing in that it will improve, or at the least, diminish some of the issues that are contributing to the Anthropocene.

The second article I’m going discuss is called “What is The Future of conservation” by Daniel Doak and his colleagues. In his article, Doak focuses on a concept called “new conservation science,” referred to as NCS. Though Doak is clearly in disagreement with the NCS goals and motives, he thoroughly describes the intentions behind NCS as well as why he disagrees with them. According to Doak, “The shift in motivations and goals associated with NCS appear to arise largely from a belief system holding that the needs and wants of humans should be prioritized over any intrinsic or inherent rights and values of nature.” With that said, it is clear that NCS advocates are in favor of utilizing nature’s resources for the sole purpose of benefiting humans. In other words, they are relying on the instrumental value of nature opposed to the intrinsic value of nature. Also stated in the article are a couple of the remedies that NCS advocates are calling upon in order to have more success than the old method of conservation, one of them being, “The primary objective of conservation should be to protect, restore, and enhance the services that nature provides to people: The ultimate goal is better management of nature for human benefit.” This statement again supports the NSC views of favoring instrumental value. Ethically speaking, NCS advocates believe it to be morally right to grant human welfare priority over the protection of species and ecological processes. In rebuttal to that given stance, Doak brings up the concern that if the primary goal of conservation is to promote human welfare, then who is going to work towards protecting and restoring the rest of nature, especially the parts of nature that do not directly benefit humans? With that said, I would have to agree and disagree with Doak’s ethical views on the issue. I agree with him in his concern with protecting other parts of nature that may not benefit humans. I don’t find it ethical to completely neglect those parts of nature that do not benefit humans; for example, diverse species that may seem to be useless. Although they may seem to be that way, there is no reason to put them at the bottom of the conservation list. The extinction of species is a serious matter concerning the Anthropocene and may completely alter the ecological process in some cases, causing even more problems. However, Doak finds it repulsive to put our human needs in the for front, but in my opinion it is essential that we benefit from nature’s resources in order to survive, as long as we limit ourselves to what we really need instead of wiping out resources left and right just because we can.

“Buying into conservation: intrinsic versus instrumental value,” is a scientific article written by James Justus and his colleagues. The main point of their essay is to explain why using instrumental value to guide conservation decision making is a better method than using intrinsic value. Conservation decision making is simply weighing where and which part of the environment should receive priority conservation over another. The first thing Justus discusses is the difference between intrinsic and instrumental value. He explains that the term ‘intrinsic value’ has not yet been explicitly defined and that “non-human natural entities that are legitimate targets of conservation (e.g. plants, ecosystems) do not possess any properties considered intrinsically valuable by traditional ethical theories.” In other words, he doesn’t believe that ‘intrinsic value’ is a reliable enough term to measure the amount of value that an entity possesses. However, Justus believes that using instrumental value to aid in conservation decision making is ethically the way to go with reason that focusing on intrinsic value requires an undeveloped standard of value analysis while “focusing on instrumental value allows conservation decisions to be analyzed with the same tools as other decisions with multiple, sometimes conflicting, goals: all instrumental value is comparatively assessed without one form taking absolute priority.” Conservation decision making is a very important aspect of the Anthropocene, and it is important that the right decisions are being made. Though I support Justus’ stance regarding instrumental value’s role in decision making, I believe nature still possesses intrinsic value and that intrinsic value is what adds beauty to the earth as we see it.

The final article I am going to discuss is “Why Intrinsic Value is a Poor Basis for Conservation Decisions” by Lynn Maguire and James Justus. This article continues the thought process we have going from the previous article I discussed about conservation decision making, but it focuses a little more on why instrumental value is a better basis for conservation decisions than intrinsic value. Maguire and Justus state that, “Decision making requires trade-offs: competition among conservation projects for limited funds and personnel, compromises between preservation of biota and other human uses, and even conflicts between conservation goals.” Because they believe that intrinsic value is a very vague concept and not a good means of comparing values that is necessary for decision making, they prefer to use instrumental value because it “permits a full range of values of biota to be considered in conservation decisions.” In other words, in order to make conservation decisions, a comparative concept of value is required, and intrinsic value is unable to measure conservation values against competing demands. Summarizing the ethical stance taken, Maguire and Justus believe that conservation decision making should be done only after measurements of value is obtained, ensuring that fairness between entities exists, and also ensuring that the proper actions are being taken to elicit the most beneficial results. I agree that some form of measurement is needed to weigh the conservation options and aid in decision making and I agree that instrumental value is in fact the best option to do this. Conservation in the Anthropocene is no concept to be handled lightly. In fact, conservation plays a significant role in where humans may take this Anthropocene, so choosing where and what to conserve is vital for the future of the earth as well as the future of generations to come.

In conclusion, there are many factors that contribute to the Anthropocene, and conservation is just one of them. Caring for the environment is more important now than it ever has been before, and conservation is such a crucial part in doing just that. Kareiva and Marvier give wonderful examples of why conservation is so important and more specifically why we need the instrumental values that the environment has to offer. Even if we cannot see first hand some of the benefits nature brings us instrumentally, they are there, and neglecting to conserve certain parts of the environment could be very detrimental to humans as well as other species in the short and long run. Another very important aspect of conservation to keep in mind is what we decide to conserve. After all, humans are essentially the one’s in control of what happens to this earth, so conservation decision making is one way in which we could really impact the earth positively or negatively depending on how smart we are when it comes to making those decisions. Just as Justus and Maguire state in their articles, conservation decision making is no process to be taken lightly. We cannot make good judgment calls on which resources need priority conservation without taking nature’s instrumental value into account. Doing this is the first step to making the right decision, and neglecting to do so can be highly detrimental to the earth and to humans. From an ethical point of view, a healthy earth and a healthy living environment should be what we aim to pass on from generation to generation, and we cannot do this without conservation.

Works Cited

Doak, Daniel F., et al. “What Is The Future Of Conservation?.” Trends In Ecology & Evolution 29.2 (2014): 77-81. Academic Search Premier. Web. 29 Apr. 2014. http://klamathconservation.org/docs/blogdocs/doaketal2013.pdf

Justus, James, et al. “Buying Into Conservation: Intrinsic Versus Instrumental Value.” Trends In Ecology & Evolution 24.4 (2009): 187-191. MEDLINE. Web. 29 Apr. 2014. http://colyvan.com/papers/bic.pdf

Kareiva, Peter, and Michelle Marvier. “Conservation For The People.” Scientific American 297.4 (2007): 50-57. Health Source – Consumer Edition. Web. 29 Apr. 2014. http://ogoapes.weebly.com/uploads/3/2/3/9/3239894/conservation_for_the_people.pdf

Maguire, Lynn A., and James Justus. “Why Intrinsic Value Is A Poor Basis For Conservation Decisions.” Bioscience 58.10 (2008): 910-911. Academic Search Premier. Web. 29 Apr. 2014. http://bioscience.oxfordjournals.org/content/58/10/910.full.pdf